Global political discourse is complicated. No fancy way of saying it and I’m not clever enough to put it in a more insightful way. Half the time I feel like we know the world, and the next I’m nodding in agreement to things I’m pretending to understand.

It turns out I’m usually nowhere near as informed as I like to think I am. And yet this is the stuff that shapes the world we live in, defines our everyday, underpins every aspect of it. There’s no more apparent time than now to see this – trying to piece together the places of global superpowers in brutal conflicts. A small but nonetheless interesting effect on neo-liberal identity politics of the West during the ongoing genocide of Palestinians is identifying just how many companies that underpin our daily lives are directly complicit in supporting these regimes. Exploitation and proxy war is an every day fabric of our culture, whether we like it or not. There’s a reason it’s called ‘global’ exploitation.

So digesting these conversations, these ideas and nuanced materials is vital – and while often uncomfortable, it doesn’t need to be unthinkable. Especially when done through artistic means. In fact it should be uncomfortable, when something creative suddenly gives clarity to events many people are often too privileged to witness.

With tensions continuing to grow in international circles through presidential elections, genocide, technocratic norms becoming suddenly very public, global exploitation, brutal ‘democracy’ protests throughout East-Asia, and 100 other things that happened in February alone – I want revisit a surrealist film that was banned in the USSR for its beautifully playful and yet dangerously subversive style to show that alternate realities existed long before Meta and X.

It’s always scary to see whether we can really escape the realities we’re put into by people behind closed doors. Let’s talk about the Glass Harmonica.

To be honest, and I hate the fact I’m saying this, I only know of Glass Harmonica because I saw it in an Insta reel with some half-baked caption saying something about the 60s aura being off the charts.

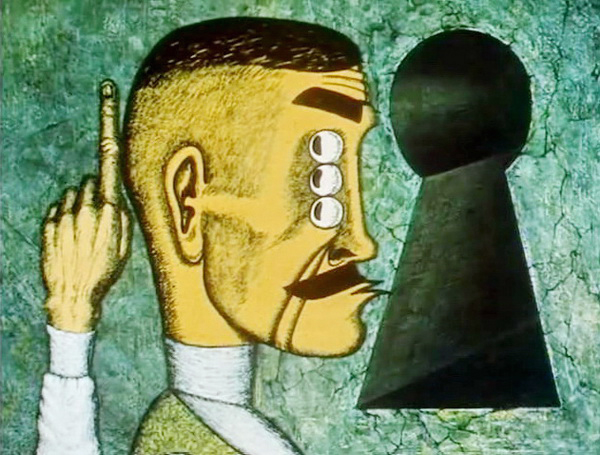

It’s a typical looking mid 20th century surrealist film – the same hand drawn animation as you’ve seen in other clips – like something from Yellow Submarine or an unusual Polish children’s cartoon you saw sampled for a music video once. But this film, directed by Andrey Khrzhanovsky in 1968, is much more than that. Banned for not meeting the socially realist mandate set out by the Soviet era government of the time, Glass Harmonica was a very specific piece of art, and a very specific but weirdly playful threat. Like a toddler with an eviction notice.

The whole film is about the observer, the one who is watching. Who, after all, is watching? and why?

Between the Texts:

Intertextuality here is distinctly physical, the adornment of references to Bosch, El Greco and namely Magritte – whose famous painting ‘Son of Man’ is undoubtedly a central influence for the design of the antagonist – the yellow devil, the man in the bowler hat with gold in his hands. It’s influences are so physical with it’s hand drawn textures and childish animation, that it’s easy to get drawn in to thinking this film is merely the sum of its parts.

These influences help to lay a groundwork to the narrative, much in the same way that discussions around socialism rely on their own intertextuality. We frequently quote the likes of Marx and Proudhon when discussing landlords, tax and political absolution in contemporary state structure. They’re the modern stories passed down from grandparents, but in a parallel language, one of cultural and political debate, one of economic reality.

The film emanates this, and I think utilises these references to a heavy degree to emulate a symbol of dream states – a signifier to tell a story. In the same way as you might see a street in 1920s New York and may draw internal parallels to stories you think you’re going to be told. Or likewise being shown a saloon on screen and expect a cowboy to come sauntering out, a place and setting that acts as a compound format through generic linguistics, the screen or the stage etc. Honestly if you show me a saloon and there’s no cowboy then I’m going home.

The Conversation:

At the heart of this is a contrast, this dream, is a children’s tale of two kingdoms. A battle cry from one army to another. Capitalism and Communism. But does Glass Harmonica provide us a way to view this conflict in a way nuanced enough to be relevant to a 2025 era of ‘oh God what if I actually do get conscripted into the army’ era?

Do these two words even mean anything? In short, no. They really don’t.

The debate has always been complex, and to portray the political discourse as two opposing forces locked in combat is far too egalitarian for anyone’s liking and in general. At best, it’s a thoroughly romantic claim.

There’s a good interview I saw discussing the the misquote, or rather, misunderstanding of the famous Marx line ‘religion is the opiate of the masses’. In it, the journalist describes how the fundamental message of this statement is a powerful criticism of religious authority by the assertion of self-realisation. That capitalism acts through the abstract, and reliance on the habitual repetitions/ development of the self are the path to avoiding the so called ‘Capitalist realism’ that locks individuals into a state of obedience to pre-determined capital economics.

Glass Harmonica is this idea, but more deeply ingrained through style. For me this is not as simple – it is political discourse but through a systematically spiritual lens. Rather than a synthetic combination of the two ideas providing solutions – it’s the convergence of capitalist and communist ideas that show working people that their own actualisation is the source of their greatest, and possibly only, strength. It is the iterations of both words in and the specters they conjure in political discourse.

What are we actually talking about? That which is unspoken is that which cannot be sold.

Glass Harmonica is evident in it’s criticism of Capitalism. The entire sequences laid out in darkly, monty-python esque animations of people chasing money and possessions, the man staring through the keyhole at treasure, using his wife to prop up the assortment of bizarre, ancient world riches he’s collected to add value to his dismal home. Indeed, Glass Harmonica contains an entire sequence where it’s townspeople transform into hideous creatures and tear each other apart, in some form through dance, in some form of barbaric cartoon savagery.

But there are echoes of communist reality here also. Leninism, Stalinism, Khmer Rouge, you name the failures of the broad terminology and they’re represented here – the real histories of communism are echoed by the snitches. Characters in the films who grass on others to be paid handsomely by the yellow devil himself and the tall, dark figures who make people disappear. These stylistic choices in the film seem to deliberately evoke a ‘purge’ essence which is all too familiar.

Perhaps then this Soviet dream state is more an affirmation of the opposite to what Marx meant in his quote, or rather a delamination of it. The abstract isn’t the tool of intellectuals but of those at the heart of experience, of political thought and ideal, of reality. Those who build, not those who preside.

The sheer reach of psycho-polictical capitalism is evident through the untouchable ideal of the brand, the influencer, the trend. But likewise, Glass Harmonica reflects that examples of communist thought corrupted through abstract political focus on generally relativist policies to push forward national identity are as much a corruption on civil right as its capitalist counterpart. In fact, does the idea lie in other abstracts and experiences? Alternative realities.

It’s a term I think most of us are familiar with. Whether it’s through the products of Silicon valley, Blackrock or Elon Musk’s cyber-punk ‘Arasaka-esque’ virtual comprehension technology – we know the many heads of the snake. But alongside these ideals, the unobtainable traditional advertising standards, does the answer in fact lie in the same method as the problem? A prevailing thought in contemporary socialist dialogue is that extracted from Mark Fischer’s (very over-relied on) Capitalist Realism – that we in fact need to understand the reality that there are alternatives beyond our political paradigm, and that it’s encompassing nature has only the pre-requisite of us believing it.

Glass Harmonica shows it’s townspeople, the collective consciousness surrounded by a dream. Through an albeit playful theatre of colour and movement, it shows them within their material reality, but also as the subjects of abstract thought – a dream they did not create.

In turn, the instrument itself of the glass harmonica is the enlightenment of people. Now the film depicts this in the cliched Western enlightenment rhetoric (the classical instrument, renaissance figures, you get the idea) but even so their literal ascension into the sky is through thought over action, the ethical over the imperative. We even see a man donating his clothes and transform as he does so from the aforementioned monstrosity in a way reminiscent of the Buddha. Much in the same way as commercial space can never be truly real for those outside of the corporate, the people’s town in the film only becomes theirs when they have truly built it.

Thought – but more importantly action beyond ourselves leads to an alternative. Not necessarily better, but an alternative – a thought echoed so clearly and poignantly when the townspeople don’t react to the Yellow Devil’s golden hand, and instead come together in their new forms to rebuild the clock, rebuild their understanding of the world they exist in, rebuild their beautiful little world.

So what?

Art has it’s privileges and bias, but Glass Harmonica is one of hundreds of films like this. One that takes a material reality and squeeze it through distinct cultural style to ask – is this it? There is no definite conclusion, but only the hope that one exists in a place we haven’t reached. The hope that the journey there can be determined by our own dreams, and not those forced on us by states, empires and Gods.

Watch Glass Harmonica, or don’t. I know that one thing we can all do with remembering is what of ourselves exists within our art? And if art is our reality, what can we learn from observing ourselves in it? Do we in fact, just need to listen more closely to what’s clearly already happening around us. Maybe there is more action than we think that can be taken to rebuild our own instruments of effect.

Actually om second thoughts, do watch Glass Harmonica. It does something to the surrealist in me that feels like popping bubble wrap, and hopefully, if nothing else, it does that to you too.

Leave a comment