A few weeks ago, a friend invited me to the cinema. I thought about it but then I remembered it was chucking it down with rain, and that I’m generally pretty broke at the minute.

Saying that, my only other options for the evening were work, cleaning or trying to re-pressurise my boiler. So, half an hour later, I found myself sat in the cinema.

It’s the Savoy Cinema in Nottingham, UK. A fantastic independent cinema that you should visit if you ever come to the city. The film is something I’ve always wanted to see but never actually sat down and taken the time out to watch – this showing being a celebration of its 35th anniversary. The evening then turned into one of the most special cinematic experiences I’ve had in a long time.

Within the first 15 minutes it had captured me. The sprawling cityscapes of a dark and gritty cyberpunk future. Bike gangs chasing each other down through the streets of Neo-Tokyo to a mesmerising soundtrack, fires burning through the blazing neon alongside a level of spellbinding imagery that held my attention from start to finish. I barely thought about anything else for the duration of the film, it completely and utterly captured me.

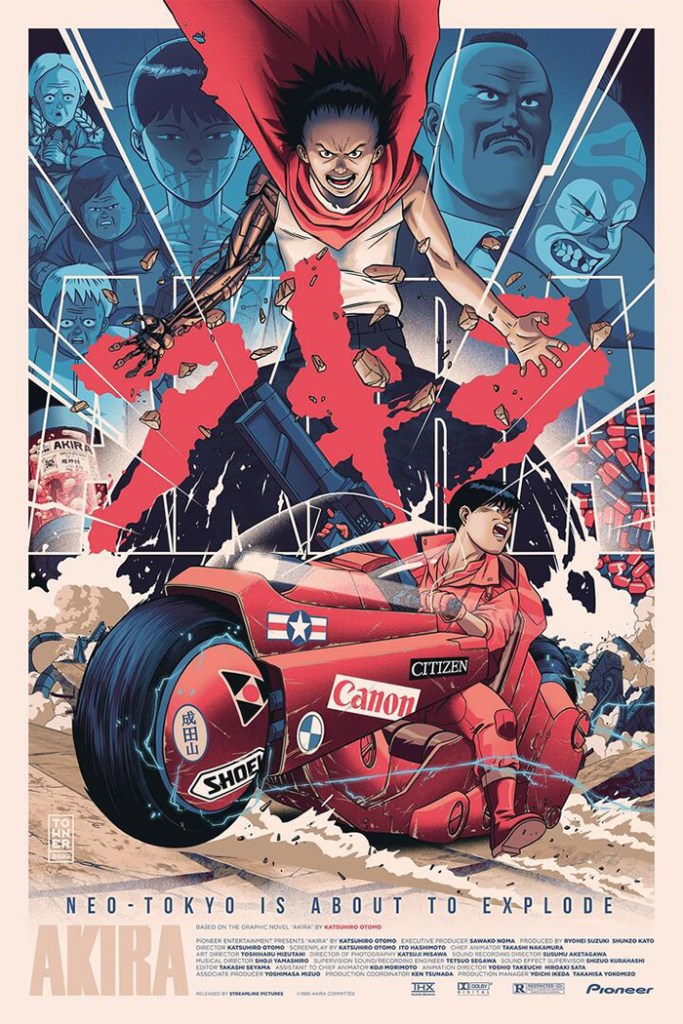

This film was Akira.

Akira is a 1988 Cyberpunk anime film, directed by Katsuhiro Otomo, based on his 1982 manga of the same name. A legendary example of cyberpunk and animated cinema, it follows the journey of a group of teenagers navigating the chaos of a dystopian version of Tokyo, rife with civil unrest, criminal syndicates and a monstrous government conspiracy of unprecedented scale. I came out of the cinema unable to really gather my thoughts, as I was looking around the audience members, who felt like pockets of people from every age and walk of life.

But rather than diving into the film itself, I want to talk about the point that Akira makes as a film. The invaluable lesson at the heart of it which remains relevant to the industry even today.

Making a ‘point’

The original manga series had found some success, and it wasn’t long before Katsuhiro Otomo was approached with the initial deal to animate his work into a feature length piece. A dream opportunity for many creatives. While initially denying the opportunity to animate his work, Katsuhiro eventually agreed to the deal provided he could retain complete creative control over the work.

The film is produced by the Akira Committee. A fascinating group of several major Japanese production companies who came together specifically for the creation of the film, gathering an incredible ¥1,100,000,000 budget for the project.

The cost of the production is evident, with Akira holding roughly 160,000 animation cels, including individual animation of characters lips, clothing and small term objects like bits of rubble or embers through super fluid motion and digitalised action movement recordings – the team of 60 animators could see everything before rendering into cels. They even made 50 individual, unique animating colours for the sole purpose of bringing the Neo-Tokyo skyline to life.

Even today, this is highly unusual for any studio to carry out, whether it’s major anime labels like Studio Ghibli and Studio Trigger, or your major Disney Pixar blockbusters. It’s evident to see in breath-taking scenes of crowds in riots, centered around burning pyres and Buddhist preachers yelling out into the neon skyscrapers.

It’s easy to reel off statistics and trivia behind the production of a film, to seek to elucidate its wider place in cinema through contextual tid-bits, but it doesn’t go far enough to even begin deconstructing the sheer cultural impact Akira has had on anime, science fiction, and films in general.

Industry Standards

Every element of Akira is unprecedented. The technicality of its production is not only vast, but also uniquely specific by today’s standards. We often draw up the tired comparison between blockbuster cinema and independent films, always assuming that if you have the money, you don’t have the creativity, and if you don’t have the latter then you’re probably working on a pretty tight budget.

But Akira did both, as well as having what was essentially a major corporate merger at the heart of its operational side, it gave the original artist and writer complete creative control. While this can have its dangers in relying on a certain degree of ego to edit a film, it doesn’t seem any riskier to work to this method than allowing, say, Scorsese to produce a 3 hour-ish crime drama on Netflix. It’s about trust, an element that is essential for any creative venture.

The most intriguing part is that it all paid off. Katsuhiro changed huge parts of his story in order to adapt the idea into cinema, ignoring large chunks of the latter plot in the manga. He sacrificed parts of his own work in order to achieve the sense of fluidity in Akira’s narrative, specific to the medium he and his team found themselves translating it into.

The even more intriguing part is when you hear people outside of anime talking about Akira. Like, for example, me.

“Anime People”

I have a roster of films and series I like that fall under ‘anime’, but I’ve never called myself an ‘anime person’. I don’t know why because I’m pretty sure I am. Especially seeing as recent years have gone some way to reduce the old stigma around what anime lovers look and sound like. Whether or not it still exists, we can agree that the days of anime solely being appreciated in the west in after school clubs and small-time conventions is long over. Anime is embedded as a core part of wider popular culture, with many citing examples like Dragon Ball Z, Pokémon, Ninja Scroll or Spirited Away as key memories of their childhood.

And yet here I am, agreeing with so many others that Akira is, for me, one the best films ever made.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not harping on about this out of some misguided sense of ego or pride, but rather a respect for the craft of its creation and the wider impact it’s had. That, and I just really like straight up cyberpunk in all its glory.

Countless artists cite it as a key reference point for their work, the level of complexity and detail remaining astoundingly evident even as I sat in a cinema in 2023 gawping at the screen. It acts as a certain cultural epoch, being created during a golden period of Japanese animation where countless creators were finding themselves freer than ever to create. Though more importantly than this, they were allowed to take risks.

Others films like Mamoru Oshii’s 1985 art piece ‘Angels Egg’ or Nakiyuki Osaka’s 1988 masterpiece ‘Grave of The Fireflies’, really highlight how these creators existed in a unique period. This was a time when animation had reached a common parlance within its own culture, and was now ready to expand. It was still only just being noticed in the West by commercial producers like Spielberg and Holtzman starting to glance at films like Akira out of the peripheries.

You have this distinct scenario where a genre has enough work behind it to have a base, a contextual home, but enough room to breathe and expand. Enough attention to create an active market for it, but not so much popularity to restrict what it can achieve, or rather, what is expected of it by an audience. The result is art that is willing to take risks. An industry that maintains it’s commercial structure, and yet still manages to produce genuine work – by which I mean work that has a traceable lineage to actual creators, and the wider community of people that have inspired it.

So what?

As a key point in sci-fi cinematic history, the importance of this balancing line seems just as relevant today. We were recently treated the ‘Cyberpunk: Edgerunners’ anime series by the previously mentioned Studio Trigger in 2022, taking place in the same universe of the table-top RPG originally created by Mike Pondsmith.

While it’s not had the all-encompassing impact of something like Akira, Edgeruners has been one of the highest grossing and most popular anime series in recent years. So much so, that it was a major contributing factor in increasing the sales in the affiliated Cyberpunk: 2077 video game by 18% year over year. This is what stands out for me, as the video game from critically acclaimed studio CD Projekt Red had one of the most disastrous launches in recent memory, producing what was often dubbed an ‘unfinished product’ due to the sheer strain its developers and programmers were put under.

Here we see again an example of unique creativity being given space to breath in a space that is funded, and established. Likewise with the videogame Cyberpunk: 2077, we see an example of creativity having strict expectations which cripple any planned attempt at creative risks. Studio Trigger are an already successful anime producer, and yet the Edgerunners series creator (alongside the contributions of Pondsmith) Rafal Jaki, was relatively new to industry – more specifically, not having any particularly acclaimed work on the same scale. Now he’s responsible for one of the most successful anime series since Attack on Titan. So yes, the guy’s done pretty well.

The point here seems simple, and it’s one we keep saying again and again, in yet more inventive ways to just try and hammer the point home. Creators need funding. They need space and time. They need support and they need opportunities. But they need to be able to take risks, despite what’s expected of them.

Yes, this is obviously a business, it’s an industry. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t be better about how we build its future. Creative industries worldwide need to simultaneously embrace creative risks to achieve distinct works of art – while also keeping the market diversified with poplar, safer works (Marvel Cinematic Universe etc) as well as regulating how we produce these. Incorporating structures whereby taking risks and, at the very least, investigating uncertain horizons becomes a fundamental business principal, rather than a day dream.

Contrary to popular belief, these things can exist simultaneously. Commercial and independent art have a place together, to create a sphere of influence that benefits creator and audiences, diversifying what we create and what we interact with as consumers of creativity. If watching Akira proved anything to me, it’s that we have lessons to learn from its example, as well as countless other films like it. More than anything, Akira is respected for its sheer scale and creativity, proving more then 30 years ago, that the two don’t have to exist as independent functions.

You’ve probably heard people far more eloquent and convincing than me say it, and yet still it seems like a struggle in art, cinema, theatre, music, videogames – all of it – to put these processes into place. Funding bodies and newer companies certainly try, and I can’t deny the progress that’s come in terms of funding grass root artists in countries worldwide, but there still seems like such a distance to travel before this becomes an industry norm.

If Akira tells us anything, it’s that there is always more work to be done. We can and should always do more to take risks, support creatives and engender a power within artistic practises. We should always be striving to have a lineage to artists within our art – in order to take those risks which really do bring the greatest rewards.

OTHER ARTICLES:

https://www.vectornator.io/blog/akira/

AKIRA is a Spiritual Experience

Leave a comment