As much as we want to play it cool, we find ourselves occasionally coming across figures whose influence is undeniable. What better person than this as an example, and what better time to be uncool about film-making than now.

Many of our favourite artists are described, in some form or another, as visionaries. What does this mean? Does this imply they’ve specifically tapped into something previously unseen? Does it exist purely in reference to a perceived canon? It’s often dished out most in the abstract genre, more commonly you’ll see artists receiving the honorific who verge on the side of the bizarre.

Saying that, this could all just be because I’m in more of a bad mood recently after receiving a fair few rejection letters for some of my most recent scripts (probably that.)

BUT let’s nonetheless dive into a man you’ll have seen, but might not necessarily know. Let’s take a whistle stop tour through, the incomparable, Stan Brakhage.

Where to Start?

So rather than discard the term, I want to take a closer look at it, because I think there’s a kind of casual genealogy to why we use it, or more importantly, why it’s right for us to use the term outside of honorific practise. There’s a traceable line between its casual adjective use and the central idea at the heart of its usage. Furthermore this gives me an excuse to cover someone I’ve wanted to discuss for a while now. I can think of very few practitioners who are better suited to the visionary status then the American experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage. Now here’s a good one.

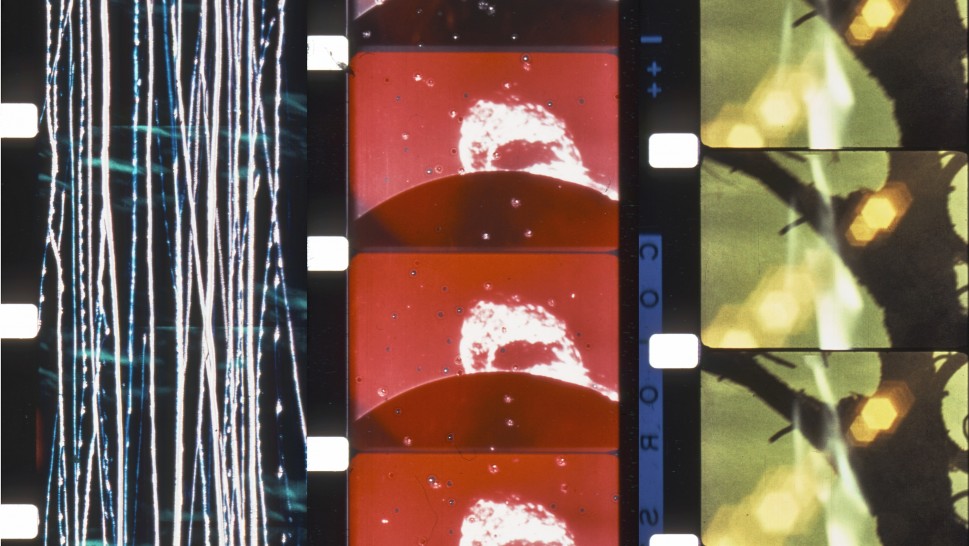

Brakhage was an avant-garde, American filmmaker who created and directed hundreds of short films over the course of 5 decades, creating films in the 50s but really only beginning to receive critical praise for his work from the 60s onwards. His films utilise countless techniques to evoke striking, bold artistic effects, often painting on the celluloid itself, scratching the film and utilising multiple exposures in order to become arguably one of the most influential filmmakers, and earliest practitioners to extensively use these techniques, throughout the US. His films cover such a huge range of topics, that it seems derivative to list them all, but each one shares the common expression of lyrical and transcendental style through which to speak to a viewer, often silently yet manically.

As always I’m looking at this in a potentially annoyingly subjective manner, but I suppose the first thing to get out of the way is that I don’t necessarily like all of his films. Some I find don’t ‘hit’ me, they don’t evoke any kind of sense in me and to be honest I think that’s partly the luck of the draw. Brakhage has a huge discography of films, many of which are available on YouTube and other, less-well known online services (which I’ll put in links at the end.) It’s bound to happen with such a huge collection. However I’ve selected some of my personal favourites which, helpfully I think, go some distance to outline what I’m trying to say about him.

Experimentation:

The first thing you consider with the term ‘visionary’ is a metaphorical, sub-structural definition. The transcendental aspect of work that goes beyond a perceived notion of what art is capable of, and additionally, what cognitive forms of expression are capable of. You see that’s exactly what Brakhage does, his films are pre-cognitive. It reminds me of my discussion on Elias Merhigue and the 1990 horror classic ‘Begotten’, likewise Brakhage relies on conveying a sense of a story rather than what we’d traditionally conceive as a story in itself.

I can feel how pretentious I’m being, so please bear with me.

The ‘sense’ of a story is what essentially drives a plot, while relying on the plot structure and dramatic ‘beats’ to drive it’s essential nature, as you’ll see in the any creative writing 101 video on the internet. Yet to pursue the abstract, we willingly negate this format to express that ‘sense’ through a different structure. We aren’t really changing the process in a generalist sense, but more replacing dramatic beats with visceral beats, beats that rely on a viewer coming to their own moments of experiential prospect through observing the piece. Surrealism seeks to evoke the same emotional response through radically redefining the status of cognitive formatting, but basically leaves the traditional relationship between subjects and object the same. The risk is always creating a kind of ‘metaphor fatigue’ in a viewer in which the visceral beats are missed or misplaced and the observer becomes disconnected. That’s inevitably what happened with me on some of Brakhage’s work, and yet when those visceral beats hooked me, they dragged me deep.

The benefit of this technique is that when you have a viewer hooked on visceral beats, then you can take them to places that other scripts/books/films etc. can’t reach, or more specifically, would require far more space and time to achieve. Brakhage, at his best, is so successful in the delivery of the transcendental narrative, that you don’t even realise he’s doing it. So here, I suppose ‘visionary’ refers to this romanticised, self-relinquishing, experiential system yielded in order to convey greater senses of theme and metaphysical enquiry that cognitive forms like language have no hope of really getting to the heart of. Brakhage is almost entirely pre-cognitive, and that’s why the lyricism in his work is so touching. Let’s take a surprising favourite of mine, ‘Desistfilm’ (1954). A 7 minute short following the events of an adolescent gathering which includes drinking, sexuality and, playing a mandolin? I’m honestly not sure.

The Fear:

‘Desistfilm’ is frequently referred to as a poetic object, as much a metaphorical narrative as any of his other work but arguably within a slightly more grounded set-piece. Here we have actual people, characters to focus on in a physical sense, rather than a distant, emotive nature surrounding us. Interestingly, this is one of the only films with sound – a rather disturbing, foreboding chorus that can best be described as a nightmare fun fair in slow motion. The film follows the hyperbolised interactions between the youth figures, a basic premise that still manages to eclipse the practical occurrences. By that I mean that his film, through the shot-tracing, through the soundtrack and the usage of actors as physical symbols more than literal people, we are immediately handed the ‘sense’ of adolescence on a platter. What is conveyed to us is the idea of meaning, a symbol that reflects the shadowy core of something unfamiliar. The ‘sense’ of the drama lies more in the exposition and deconstruction of symbols, a raw emotional sense which we find ourselves spinning in rather than something a character or set-piece tells us. The individual movements of characterisation seems skewed and entirely victim to the camera. The ‘vision’ sense here is in the pockets of movement in dark corners of skulking figures – and yet we’re so acutely transfigured from this state into one of understanding by Brakhage, as he captures these carefully wild expositions so that we translate the images before us into a story, without the need for reasoning post-cognition.

Likewise in ‘The Way to Shadow Garden’ (1954), a roughly 11 minute exposition of a man undergoing some kind of ritual terror in order to access the aforementioned ‘Shadow Garden’, the metaphorical is rammed at the forefront, initially seeming as the ‘initial’ often does, the definitive theme. Yet there is malevolence brimming behind every aspect of the initial presented in front of us. The prime example being the brief logline I gave of the piece, none of which is explained. So how did I come to that conclusion? Have I purely inferred it based on my own pre-conceived notions? Yes undoubtedly. Once again Brakhage continues his exploitation of biased perception, and instead he tries to establish the sense of an untrained eye, a sense of the perceived that’s unaffected by modern preconceptions. His focus on this theme throughout much of his work is unshakeable, but ‘Shadow Garden’ has such a distinctive lead to its climax, that it feels even more provocative. Brakhage is constantly fascinated in exploring what is often forgotten through contemporary forms of experience, the relentless consumption of fluid media that is instead replaced here by an unseen narrative of worlds that we could see, but choose not to.

So what now?

This is what Brakhage relies on and really why he perhaps earns this title of ‘visionary’ in a metaphorical sense. The liberality is so striking that it rips you out of your world and shoves you into his, following a deranged man in a room as he gouges out his own eyes and is transported to Shadow Garden, a garden in negative filter that’s drenched in the dark blue and white tones so naturally linked to subversive themes. The negative filter is probably the most consistent method of conveying that sense of abstraction and deconstruction with the avant-garde, and so becomes clichéd in contemporary fields.

But that’s just the thing, Brakhage was such an early practitioner of these styles, that it’s no wonder he was inducted into countless art galleries and New York film events following the beginnings of his career success. Brakhage creates a conceptual space through which we feel as if we’ve created our own ‘beats’, despite the fact that Brakhage has very much guided us to them, he refrains from ever inducting our ‘eye’ into a structured, stable system. This is true throughout the art itself, to the distribution methods of his cinema and the independence of his creative process. It’s the classic guiding a horse to water scenario, and part of what makes his art so mesmerising.

Though I would go even further, or maybe less far in the first place, and argue that the ‘visionary’ has an essentialist nature we can easily ignore if we’re not careful. The visual aspect itself.

Yes I know, please do bear with me.

The Hypnotist:

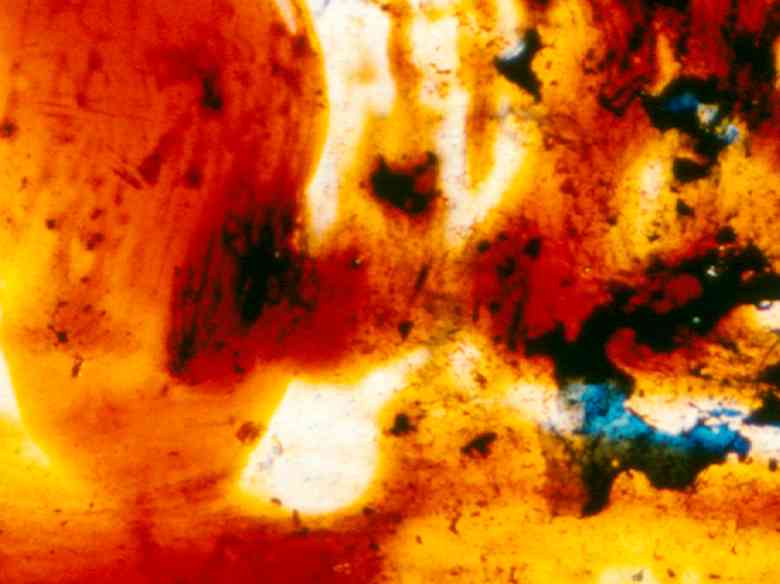

A huge part of Brakhage comes down to something even more than pre-cognitive space, and that’s the path forged to it. The visuals are just viscerally striking, beautiful. His films are mesmeric, especially the later in his career you get. He uses those earlier, physical techniques to add effects to his visuals that are so rarely used in contemporary circles, which is such a shame as I think they’re a hallmark of independent film-making. Take either ‘Mothlight’ (1963) or ‘The Dante Quartet’ (1987), both of which rely on visuals that are wholly abstract, shapes that seem more like paintings flashing before you in chaotic freefall, qualified only by their titles, or in the case of ‘Dante’, actual ‘chapter’ cards. These experiences are sublime, definitely not everyone’s cup of tea, but if you’re in the right mind-set, then it becomes the closest visual link to an out of body experience I can think of. It illustrates Brakhage’s long running relationship with the surreal, and the path that filmmaking leads to it. He even expressed in one of his essays on the art form that film is the closest genre in bringing an audience in proximity to the divine.

So then, what does that mean? The ‘right’ mind-set? Well part of relying on visuals and meta-narratives beyond cognitive spaces is that it’s easy to miss those visceral beats. It’s incredibly easy to lose your audience if the visual cues don’t conjure up the desired effect. Though the fundamental misunderstanding to overcome is that these desired effects are rarely specified themes. Brakhage works with very specific ideas such as work, life, death, sexuality, innocence, family, rebirth, spirituality, but I would happily argue that matters little when observing the visualisation process itself. By this I mean that the viewer’s own interpretation of these images is far beyond the artist, and yes while I’d question anyone who would argue that ‘Mothlight’ is about lifeguards in Miami, it still seems inappropriate to ignore that power that these kind of manipulated visuals have, and why their ‘missing’ of a beat can so quickly detach a viewer.

In this sense, the practical visualisation of Brakhage’s ideas stimulates a lyrical obsession. His films are most definitely poetic objects, by which I mean they are interpreted conceptually, explosively. His work provides a canvas saturated with visceral thoughts that form a single shape. It’s like having a table full of living jigsaw pieces that someone tells you can be constructed as a whole shape, only it’s a shape you can’t see when whole. There is a definite contextual paradox in his work, and the more you try to dissect it, the harder it becomes to perceive.

Are we really using the word ‘poetic’?

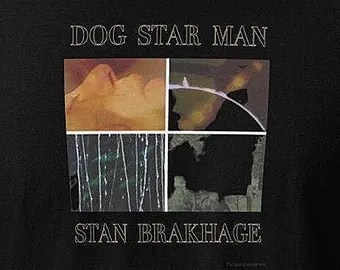

Unfortunately that does mean that I find it very hard to write on Brakhage, because the more I try to interpret him, the further I get away from the point. But this in turn seems to be the most visionary part about him, and I think why I’m not wholly rejecting the term. To me, ‘Visionary’ does refer in part to the metaphorical narratives that reject traditional format, but they are also works that access that specific pre-functionary aspect of the brain. The old, ancient brain that sees shapes in the dark and hears voices in the fire. No Brakhage film encapsulates this best than his most well-known piece, ‘Dog Star Man (originally filmed 1961-64)’.

‘Dog Star Man’ is a compilation of previous shorter films or chapters into a 1hr 10 minute piece, and it takes everything we’ve said so far in order to achieve it all in one piece of cinema. At its core, it tells the same visceral beat story, focusing on a man taking his dog up a mountain to chop down a tree. In itself this image is primal, possessing a seemingly fundamental narrative for an experience that trespasses our high mental concepts from a contemporary standpoint. From this position, Brakhage unlocks roads beyond the rational, and into the transcendental, the spiritual and the divine. To paraphrase the man himself, this is where cinema becomes a point of revelation.

The whole film has the man (played by Brakhage himself) journey through seemingly incoherent yet unified visions. The style of filming , the practical effects, the weird shots of a baby moving inescapably close to the camera, the foreboding shots of a dark sun burning, all of it both burdens and unburdens us. The visions are thick, and yet they are the sole form through which the character progresses, therefore they are the sole form through which we progress. So in addition to the first half of visionary style, Brakhage expands from the idealistic core and into the lyrical, the poetic, the stylistic. The visuals are what transports us, not just because of their surface level motion and physical disparity but because of their fundamental ties to the metaphysical. Here we establish more than just a symbiotic relationship which we’re all too used to in the realms of the abstract, but more of a loose connection, a correlation even that pre-supposes any notion of it existing at all. Rather than what our trained, limited eyes want us to see, we are forced into a place of uncertainty, irrationality and lyrical chaos that dismisses the vulgarity of the trained eye.

Closing Thoughts:

Through a sense of the hyper real, Brakhage establishes the most basic and spiritual of journeys, a voyage through what truly feels unknown. It’s this basic premise that fuels ‘Dog Star Man’ and one of the quintessential structural paradigms that establishes Brakhage as visionary. Not because of the acclaim of the sense of artistic/ haughty merit, but for the purist use of the visual in the practise of storytelling, and for the uniqueness of his exploration through the passage of unconscious and conscious knowing. ‘Dog Star Man’ creates a space for experience, a place where our perception, all that we expect and ‘know’, is torn apart and laid as the path towards something beyond that. It’s not so much that our sense are negated, but instead they are incessantly expanded like a wildfire.

He is visionary in an essentially genre-focused sense, a structural sense that acts as the lever on which his ideas and concepts pivot. He is both severe or intense, as well as playful and fundamentally interested in exploration. His films pushed the boundaries of what was ‘done’ in cinema, undoubtedly influenced by his contemporaries but managing to cut out a career for himself, founded on his own visions. It’s easy to do what I’ve done here and sound needlessly pretentious about it, but that’s just the idea, I can’t describe to you what these films are like because it’s entirely something you’ll need to experience for yourselves. Language does nothing to accommodate art like this.

Visions are the unspoken. They are what we can spend years of our life trying to articulate because the feelings are simultaneously basic, and infinitely complex. Loving and hating someone at the same time, inspiration, redemption, sexuality – all of these complex ideas that are ubiquitous and yet so hard to truly perceive or describe in a linear sense, they all flourish in art like this.

To be visionary then, from an artistic perspective, is to express these base feelings and convert them into illusionary forms. These perspectives both deconstruct and redefine sense, relying on narratives like those of Brakhage to expand pre-conception into a space that accommodates observation but asks us to leave our pre-conceptions themselves outside at the front door.

Even if this undermines the entire post, and seems needlessly blunt, I’d have to say just go with it. Probably best not to ask questions, they’ll do nothing for you here.

Other Bits:

- BRAKHAGE’ – Jim Sheddon documentary exploring the breadth of Brakhage’s work – https://vimeo.com/89929766

- Short article on the essays of Brakhage, and how he surpasses the capacity of academia – https://brooklynrail.org/2004/09/film/telling-time-essays-of-a-visionary-filmmaker

- ‘Stan Brakhage’s spiritual imperative : its origins, corporeality, and form’ – essay by Marco Lori (2017), courtesy of Birkbeck, University of London – https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40257/1/Publicversion-2017LoriMLphdBBK.pdf

Brakhage Films:

- ‘The Wonder Ring‘ (1955) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uD7uqs4y7tQ

- ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ (1981) – https://vimeo.com/244464831

- ‘Dog Star Man’ (1961-64) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lb5Ko_sTwlc

- Brakhage anthology (Criterion set in case you fancy purchasing a definitive set.) – https://www.criterion.com/boxsets/722-by-brakhage-an-anthology-volumes-one-and-two

1 Pingback