What the f*** does Post surrealism mean?

In my defense – when I said this, it was:

- 8am on Tuesday.

- We were on our way to work.

- I had lost my keys.

- …Was also generally in foul mood.

While I might have been a bit harsh when Faizah decided to start talking about Post-surrealism at 8am on a Tuesday – I maintain that, even in the best of times, it’s a term that just sounds a little bit vague (and very pretentious.)

It is, to some, one of those terms that’s thrown around to describe pretty much any abstract work at a certain point of the 20th century, and contextually that’s kind of true. But the origins are actually far more specific, as a wider historical break in both thematic and stylistic drives within the surreal genre, arguably one of the most significant of the 20th century depending on your perspective and what vibes float your boat.

Post surrealism has some lessons, and some absolutely golden nuggets. It represents the birth of a modern understanding of the surreal genre, a diversification of who was celebrated in surrealism and the first major break of surrealism in America, mainly thanks to the artist, Helen Lundeberg – as Faizah so patiently explained to me.

I heard you’re a surrealist now?

Helen Lundeberg had many labels. She did a lot of stuff that, looking back, we try to tie to her context as a human, an American, a woman – even though these things are in some ways, irrelevant. How can they be relevant to work which so beautifully rejects structural space? There’s convincing arguments on both sides.

As is always the way, the categories we use to specify and qualify an artist’s existence are numerous and symptomatic of our division of their ideals down the line. It’s diversification, and potentially dilution. Yet this in itself is her composition, a continued abstraction of functional parts into simplistic terms which, in their simplicity, become wholly obscure, separate and potentially arbitrary.

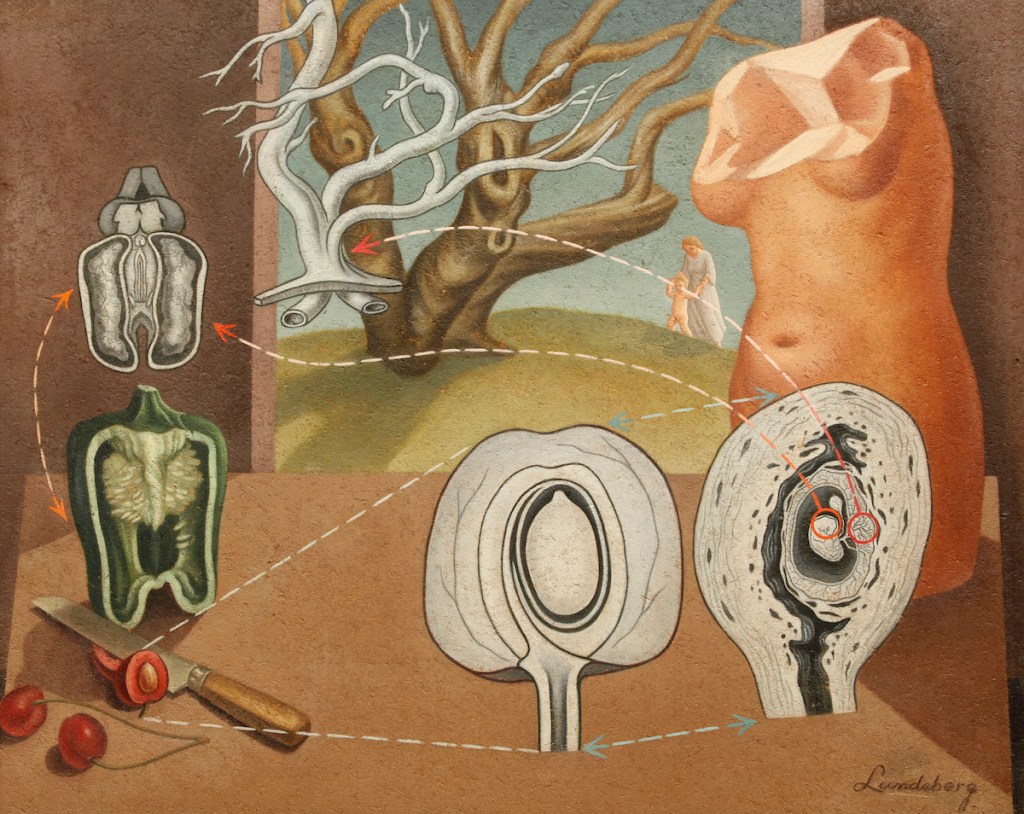

Lundeberg was born in Chicago but her family moved to Pasadena, LA in 1912 – the city to whom she become so invaluable to for the development of its abstract art collectives. Her career stretches a colossal period in American history, producing work from the 30s all the way to the 80s. Her career also has several breaks and separate approaches, changing the course of her stylistics over the decades to eventually focus on different artistic ideals. In 1934 she painted the famous ‘Plant and Animal Analogies’ which can be seen below.

Her influences become immediately apparent, the composite parts arranged in static, chaotic order with a clear path as if the image is being narrated for you. The symbolic is rife, and it’s a thickly textured piece that not only invites you within its structure for analysis, but abjectly demands it. Believe it or not, this painting represents the birth of what we would now classify as ‘post surrealism.’ Alongside this work, Lundeberg and her husband, the famous hard-edge painter Lorser Feitelson, published the ‘New Classicism Manifesto’, a work that would go on to define the further development of surrealism in America, and arguably towards many of the famous art figures of the 1960s.

So now you might ask what exactly new classicism is, and if it’s surreal, then in what way does it re-interpret the function of the original surrealist manifesto?

New kids on the block

The manifesto was labelled as ‘new classicism‘ following Lundeberg’s own roots in social realism and wider abstract art. It was the critics of their work that referred to it as the ‘Post Surrealist manifesto’, recognising its influences and fundamental drive, which I think is fair enough considering its artistic function. The manifesto is focused on establishing a new attitude towards surrealism. I’ve often spoke before about the neo-surrealist approach to establishing meaning or metaphoric significance within surrealism, allowing a kind of self-initiated analysis to take place which yields some kind of emotive conclusion or, dare I say, ‘meaning’.

Lundeberg and Feitelson sought to establish an ‘in the moment’ narrative in their abstract works. Lundeberg would establish surrealist composite parts but arrange them in a specific order to guide a viewer through the art work, and lead them to an eventual metaphorical conclusion. She inserts meaning and structure into her art, while retaining the stylistic of the un-structured ultima. Her artwork doesn’t necessarily hold your hand, but it’s laid out a very specific path for you to walk, and while her work provides stimulus for conversation on the significance of its elements, it very much retains singular meaning, or rather specific sets of meaning.

Unlike the original surrealist manifesto, Lundeberg’s work is psychoanalytic. It’s less interested in dream logic, and more concerned with the human psyche in its relationship to wider conceptual structures, the fundamental connection between the pre-functional and conceptual. This often undermines other narratives that seek to explain the development of surrealism in the US as a result of European artists feeling the war and setting up shop in America instead. This is of course a potential factor, but seems far too simplistic and limiting as an explanation for the development of abstract art within the country.

We’re also just big fans of anything which doesn’t attribute all value of surrealism to misogynistic psychonauts in Parisian cafes. Yes Breton, we’re looking at you.

Post-structure

Lundeberg represents a very early, explicit articulation of injecting narrative structure and analysis into surrealism. It’s an entirely personal choice as to whether this is something you prefer to the original illogical focus of the genre, or whether you find this interpretation to be a devolution of the concept. Either way, it’s undoubtedly a concept that heavily influences our contemporary understanding of surrealism, and indeed, I see neo-surrealism as simply the marriage between the two manifestos under the umbrella of modern influences e.g. technology, attitudes towards sex and hierarchical/political structure etc.

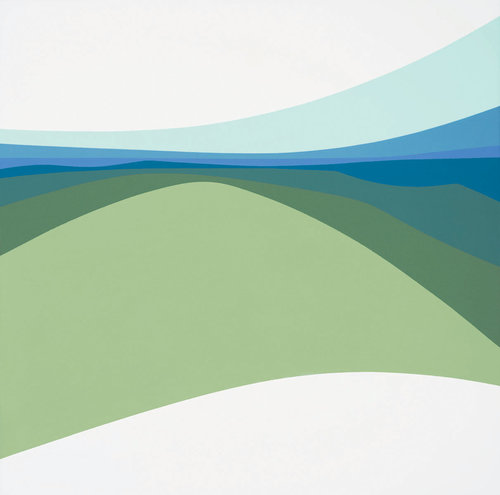

Personally, I begin to lose my love for Lundeberg post 1950s. It’s during this period that Feitelson and her begin to focus on abstraction via work with acrylics. We see a definite shift in her artwork towards deconstructing concept into abstract, physical matter, relying on geometric shapes and pastille colour schemes to create a type of legato style. This style, for me, becomes wishy-washy.

While I’m all for the use of geometric opposition within art, I find that it simultaneously relies on all the other concepts surrounding it for the piece itself to float. It must either be complex enough for me to loose myself in it, or so stark in its simplicity that I can’t help but stare at is. I don’t find either of those things with her later work so I tend to avoid it, though obviously this is only due to my personal tastes, and I nonetheless respect the drive towards abstraction as a wider concept, as well as its psychoanalytic tendencies.

Her earlier work however, throughout the 30s and 40s is undoubtedly my favourite of Lundeberg’s. Selections from both periods can be found below –

It seems potentially overt, but her work relies more on oil paints and canvas composition at this point and seems to have a thicker texture generally, while remaining light in its contrasting colours and shapes. This appeals more to my own sensibilities, viewing the ethereal skies, the deeply coloured abstract structures and figures fusing together to create artwork that sinks through you like being drenched in cold water.

Her earlier work is certainly more traditionally surreal, despite her post-surrealist outlook. The composites are arranged for a particular narrative but appear as illogical and unreal as any other traditionalist surreal painting. Her works always have a sense of ‘wash’ over them too, like a mist that slightly obscures every detail from view, enough to make your peer closer while simultaneously viewing the image holistically.

The Detail

We see this in pieces such as ‘Untitled Composition’ (1943) and ‘Pears and Pitcher’ (1949) which rely more on a sense of emergence than stark existential definition. The shapes phase into view from the mesh of warm colours. In the case of ‘Untitled’, the scene is light, airy and dream-like in its qualities, rendering a kind of simplicity that draws you to the details of every shape, but also into the significance of the shapes in relation to the wider piece.

I suppose it’s here we see her manifesto come into effect, where each abstract element is constructed in relation to the rest of the piece. Unlike traditionalist pieces existing in relation to a wider philosophy of the ‘unreal’, Lundeberg commits instead to tempting an observer in with the promise of significance, meaning and interpretation.

Similarly with ‘Tree in Landscape’ (1948) and ‘Dreaming’ (1942), we are provided with a space the entails a journey of analysis. Admittedly I think we all tend to try this even with the composition of meaningful elements in ‘meaningless’ order with the earliest surrealists, But Lundeberg forges her own path in as much as she provides a scene that burns quietly with movement. There’s a contrasting darkness presiding over both these images, yet both operate within the singularity that gives them the dream-like qualities of her abstract style, while constructing a narrative in the sub-layers of her art. ‘Dreaming’ especially creates this yawning vista which accurately emanates the sense of near-impossible space in our dreams. Yet all the while, the single figure leaning on the castle walls pulsates with, at the very least, the potential for a narrative.

Even with the most abstract composites, such as in ‘Inner/Outer Space’ (1943), where the entire structure of the artwork is abstract, relaying on simplistic elements of colour and space to form a pulsating network of sensory concepts, we still understand a sense of direction. Even though earlier surreal work could provide this sensation to just as great an extent in the sense of cognitive representation, Lundeberg achieves it in an individual, and far more pointed fashion.

‘Cosmicide’ (1935 – see right) is another perfect example of this, where the image is literally framed within an portrait, containing several surreal elements that float in dark space waiting to be pieced together, relying on the process of observation for the conceptual to explode into narrative or psychoactive significance. It forensically extracts the style of the surrealists while using it to explore a new kind of composition, the ‘New Classicist’.

Thanks to Helen Lundeberg, we have the first definite articulation of a post surreal movement, and an early signifier of its presence relative to American culture. Post-surreal was just the next step. Taking the theoretical implications of arts academia and making them practical. Improving the form by returning to before the art was formalised. Before we used big words. Lundeberg takes it right back a global surrealism, rather than the exclusive property of intellectualism.

She provided a bold dedication to the abstract, as a painter who would later go on to help define the LA art scenes in decades to come. Her stylistics clearly emulate surrealist style, but compose them into a network that stands apart, building a series of illogical way-points for an observer to follow through psychoanalytic webs leading to greater metaphorical concepts.

She provides a vital point in art history, extricating a singular form from a murky past that beautifully depicts the transformative process between two generations of genre, bridging the gap between the past and the future.

“Post-surrealism sounds intellectual, but it isn’t. It is, refreshingly, the opposite”

(Faizah Ahmed – as we walked to work at 8am on a Tuesday.)

Leave a comment