Imagine being trapped in a room, the walls are made out of orange, rusted metal and there’s a large red carpet on the floor, lit only by the faint glow of a lamp in the corner. There are no windows.

In front of you is a box, and behind you is a companion, a shapeless guide of sorts who’s warned you about the horrors in the box. They’ve warned you that, once opened, untold abominations of abhorrent and nightmarish construct will flood into the room and consume you. But one day you decide you can’t take the tension anymore and you choose, against your companion’s better judgement, to open the box.

As you heave the heavy metal open and lift the lid to rest against the back wall you peer in immediately and see nothing. Absolutely nothing at all. You turn and your companion is gone but now there’s a door open at the back of the room that yawns out into expansive corridors devoid of life.

You head out to look for anyone at all and you find nothing but emptiness, only small lights glistening madly in the gloom that fade as soon as you get close enough to see them properly. At first you hear noises throughout the looping void of lateral shapes that make up the corridors of your descent but eventually, painfully, they too fade.

How do you feel? Empty? Alone? unimportant? These my friends, are the symptoms of existential dread. and of the horror behind the somewhat controversial, Thomas Ligotti.

There is terror, and weirdness and imagery of the unreal but these are only smaller facets that converge to progress his narratives to their final conclusion – that life can itself be it’s own nightmare, and truly without meaning.

“What remained lost was the revelation that nothing ever known has ended in glory; that all which ends does so in exhaustion, confusion and debris”

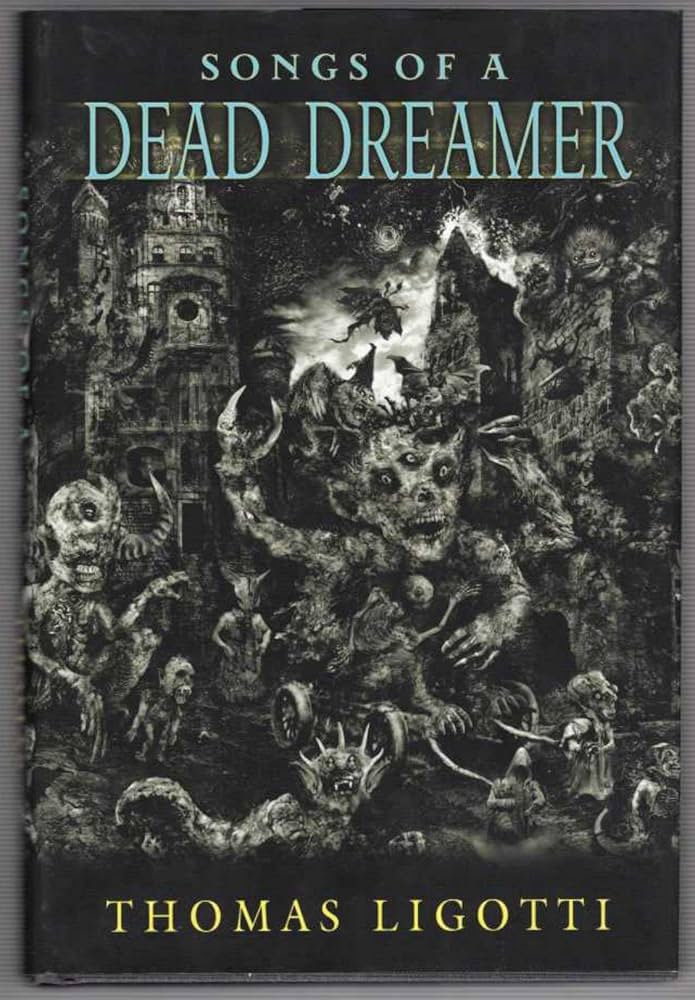

Vestarien, (Songs of a Dead Dreamer‘ – Thomas Ligotti)

The Book:

As is likely obvious, I’m fresh off the back of reading the Penguin Classics edition of Thomas Ligotti’s ‘Songs of a Dead Dreamer‘ (1989) and ‘Grimscribe‘ (1991) – this 2016 edition combining both original collections into one spine. As with everything I attempt to discuss, there are countless others who can depict the experience of his fiction in a far more articulate manner, a few of which can be found at the end in case you want more detailed reading into his works.

Ligotti is a hallmark of contemporary horror. First published in 1989 with ‘Songs of a Dead Dreamer‘, he has gone on to win every award you can think of for the genre and is widely considered one of the best examples of contemporary horror fiction, frequently quoted alongside the likes of Lovecraft, Machen and Campbell. So what is it about him that intrigues people? Because ‘intrigue’ is definitely the right word for it. People speak about him with a glimmer in their eye.

I don’t want to submerge us all into the details of his stories, as that pretty much defeats the point. If there’s one consistent thing about the collection it’s that each tale pulls you in with unnerving effectiveness, each story gives the distinct impression that you’re sinking into a pit that you might never return from.

That’s a hard thing to achieve with any anthology of stories, let alone with horror, which lends itself as much to cliches as any genre of fiction. There’s only two I can think of that didn’t interest me as much, but that was more from a personal distaste for fantasy Gothic and the world building that’s entailed in those kinds of narratives which was, in this case, laborious.

Diving into the cosmos

Already the origin of the aforementioned ‘intrigue’ becomes initially clear. He writes worlds and characters that are twisted, but not in one twisted sense. The illogical in his tales feels somehow more genuine as it does not have a single point of reference, the backbone of his text can never be viewed in totality.

He blends influences from all different kinds of horror sub-genres and covers his literary footprints as he does so. He even pens a short chapter about the writing of horror in the book itself, quoting a story he never managed to publish and, as an example, editing it according to the values of each style of horror writing, from the realist, through the the Gothic and to the experimental. The Lovecraft presence is obvious, and Ligotti’s stories consistently rely on a sensation of the unknown as the fundamental mechanism charging his fiction, though often with more of a focus on the unreal as a vehicle for tragic downfall.

His characters are mentally and spiritually alone in the sense of both their ontological perspective and the unusual physical manifestations of this framework i.e. they’re usually people who feel most alone when in a crowded room or distinct from those around them, someone who is socially isolated due to a different way of seeing the world – as with most horror protagonists.

However Ligotti enacts an exquisite narrative focus on observing the macabre in the world around us as something that pervades our existence but that we rarely choose to perceive. The characters wander through strange yet familiar places and meet voices both human and inhuman calling to them from a world of madness and symbolic resonance, where the euclidean becomes strictly esoteric and nonsensical, deriving all law from the chaotic nature of existence. This is what Ligotti sees as the true nature of things, nightmarish senselessness.

The Sad Clown

So it’s here we get a little closer to the structural composite of his prose. Ligotti is notorious for the bleakness of his worlds, and that’s what really intrigues us so much about his style. His stylistics, however lucid, are swept aside by his fundamental philosophy; bizarre mannequins, clowns and inter-dimensional cults are all fuelled by the incredible force of his pessimistic outlook, the concept that life is the truest form of horror because life is so very, very bleak.

This might seem a bit much but it’s why most people adore him, myself included. It seems to me that a fundamental and consistent trait of well-loved horror comes from it’s residing in our hearts, strictly in the sense that we perceive a portion of ourselves within the conflict. The supernatural is there to reflect and remind us of life’s trials and suffering, but it can never emulate this sensation in and of itself. The nature of the ‘beast’ as it were is one that is presupposed by it’s own nature as a symbol and a conduit for emotions we derive from our own experiences, it is the narrative moon to the sun of familiarity. No matter how phantasmagorical, the basic idea that we exist in a meaningless void is infinitely more unnerving than anything one could dream up in a nightmare. The empty box is a symbol which, above all others, scares us to the core.

Ligotti discusses this further in his 2010 philosophical work ‘The Conspiracy Against The Human Race‘, in which he explicitly outlines his pessimistic viewpoint via autobiographical anecdotes to haul us to the conclusion that “nothing in the world is inherently compelling”, that our lives are optimistic fallacies in this “dream of flesh.”

No it’s not a particularly uplifting read.

But that factor comprises Ligotti’s essential narrative strength, a prolonged sense of both realistic and unreal endeavour that feels like lying awake at 3am, overcome with anxiety from a dream you can’t remember, a sense of the box opening meticulously.

The work remains notorious for it’s pursuit of the deconstruction of optimism. Indeed, I’ve met several anti-natalists who virtually revere it.

Ligotti would argue these are nothing but moments of chemical ignition that fuel a break in existential inertia. While I understand his arguments about the potential wisdom in pessimistic philosophy but often find it’s development as an argument to be hypocritical and flawed due to its paradoxical nature. It’s important to note the darker side to this, and that in the hands of someone in a more vulnerable emotion state, as well as find ourselves in, this book could do a lot of damage.

Anti-Natalists

It’s a perspective that argues just as passionately against optimism or essentialist thought as the practitioners of those two schools would argue back against ‘it’. It’s ardent articulation defeats the idea of emotional irrelevance as it occupies the same space, so to argue that nothing at all matters but simultaneously claim that no emotion is ‘real’ from a supposedly unanimous objectivity is a contradiction.

But therein lies our fascination, the morbidity and potential ramifications of the argument fascinate and inspire us; my need to argue against him really only proves Ligotti right in a broad sense – a very broad sense mind you.

Within his fiction, this philosophy manifests to create a bleak outlook for his characters in unparalleled vastness, a single law upheld within the chaotic. The scope of his narratives is what really unnerves me, and what drives me to relentlessly unscrew the fine details of the text until I finally feel the harrowing payoff. We’re masochistic creatures, and we all have that morbid curiosity that drives us further and further down the rabbit hole.

Though it would be unfair to try to affirm that Ligotti deliberately downplays the experience of being alive within his fiction as a series of factors that barely register as existence in and of themselves. Rather, Ligotti points out a meaningless, but nonetheless bizarre and fantastical way of experiencing the horrors of his stories, and of our daily lives. Granted, this is simply a fictional device for him rather than a further addition to his philosophical outlook, but it’s a great one nonetheless.

More than meets the eye…

There is always an inference in his narratives that the world is not what it seems, which seems a stupid thing to say for a horror anthology because nothing is ever as it seems, but Ligotti maintains this sentiment in a fashion unlike others. Physically, his stories take place in the strange and foreign yet oddly familiar.

The setting, in rather Gothic fashion, is ‘uncanny’ incarnate. These places manifest through symbols of encroaching fear that grow slowly through the text, creeping up on you softly. Whether this is explored through a town in the middle of a carnival in thick fog where the inhabitants barely seem human and the buildings seem to get closer together every time you turn away, or whether it’s just in the musings of an insomniac on his late night walks, that fear is always there and it is what best symbolises Ligotti’s penchant for the savage and bizarre.

The climax of these factors leads to some of the most hypnotic segments of prose I’ve ever read. Whole pages would slip by and I wouldn’t even remember reading them because the world played out in front of me was so beautifully disastrous that I was transfixed by Ligotti’s descriptive and magnificently passionate style.

I suppose in essence, Ligotti is an author who captures us with a philosophy that we all see a slice of truth in but rarely want to discuss, in turn capturing what horror does best.

Ever the optimist

It frames experiences and aspects of what we consider to be our fundamental nature, but aspects we don’t really want to talk about. It fleshes them out for us all to see in gloom – but the gloom was never to scare us, it’s to spare us having to look at what we are most afraid of in broad daylight. He fleshes out our weakness as a species in terrifying visions with breathtaking ability.

His stories don’t exist purely to create a nihilistic dialectic but rather they achieve this while simultaneously teaching us that the world is rarely as we perceive it to be. Don’t get me wrong, my reading of his work undoubtedly affirms his predictions regarding the human ability to naively cling on to optimistic fallacy, but I can’t help but feel distinct and unnatural anticipation whenever I allow myself to be guided by the eye of this invisible author’s face as they lead me through monstrous corridors, into the chaotic, eternal silence of a dark universe.

Whatever I think of his philosophy, Thomas Ligotti achieves the evocation of this sensation like no author I have ever known.

In case you’d like some further reading, these are some great sources that flesh out the relationship between Ligotti’s horror, and wider phenomenological themes within the genre.

Leave a comment