“You were not there for the beginning. You will not be there for the end. Your knowledge of what is going on can only be superficial and relative”

Disgusting. Pornographic, un-American trash.

or…a modern masterpiece?

The last censorship court case for a novel held in America, men loving men with the FBI watching, a searing metaphor for the drug and pharmaceutical trade, Aliens – the David Cronenberg film you’ve never seen.

Some people revere it, some people loathe it. Let’s talk about Naked Lunch.

It’s like following a rope laid on the ground – you think it’ll take you to your destination, until you suddenly fall into a giant, dark hole. You’re there, clinging on to the rope for dear life.

It now points in a different direction, it’s vertical, and so now follows a set of different rules. The rope is being pulled down by gravity and you need to pull yourself up it. You need to interact with it in a strange and different way.

And you’ll do it, because it’s the one thing you recognise, it’s what you ‘know’. The only alternative is worse than darkness, it’s the absence of anything. At the very least, you know the the rope will always lead you somewhere, no matter what.

In 1959, the beat writer William S. Burroughs published ‘Naked Lunch’, a series of loosely connected vignettes that provides a story following a series of characters in an oppressively absurd and bizarre world which, although mirroring all too familiar tropes of 20th century America, seemed unlike anything anyone had encountered in prose, literary sense. But despite the political and social intrigue – Naked Lunch also tells a story of intimate and devastating detail of a gay man writing in 1950s America – an empire unsympathetic to his drug addiction.

Coming round for lunch…

The closest we get to a protagonist, is William Lee or Agent Lee. Only he, and a handful of other characters, are mentioned more than once. Each story takes place over a series of locations, fictional and non-fictional, including the infamous limbo world of ‘Interzone.’ The characters are involved in a narrative that comes across as intensely hallucinatory and metaphorical, following orgies, secret missions, dangerous liaisons and drug taking – a thinly veiled reference to heroine use through ‘black meat’. Needless to say, the book caused an uproar upon publication, and is cited as one of the last great obscenity trials in American literature.

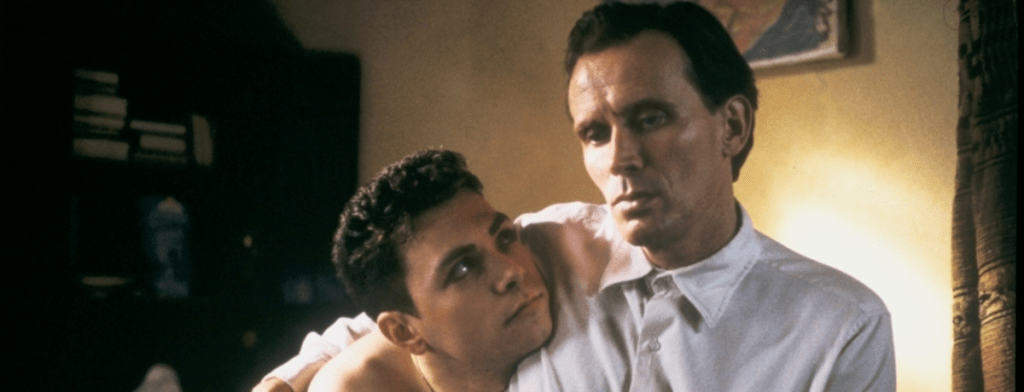

In 1991, David Cronenberg released a Hollywood adaptation of it. It’s based on the book more in style than anything, including many of the locations and some of the characters (e.g. Lee) but ultimately taking a more biographical approach to Burroughs’ own experience with drug abuse and writing the book itself. It’s important to remember that, and to remember that the film takes a far more specific view on the writing process for Burroughs, using the concepts of ‘Naked Lunch’ to explore the damage and the benefit, that writing process did to him as an author.

It’s also important to remember that ‘Naked Lunch’ is very, very hard to summarise at all, let alone succinctly.

As a film, the work has many of Cronenberg’s classic traits. There’s a reliance on prosthetic, grotesque and visceral portrayals of the ‘unreal’ within familiar physical forms. In one sense, this equates to the sweat and the heat you feel when seeing the characters inhabit ‘Interzone’ – based on Algiers after Burroughs spent much time there finishing the book.

It’s a location that is designed to have a certain familiarity to it but to also be uniquely oppressive. Every Day, convinced he is on a secret mission for the government, Lee uses his typewriter in a bright cafe full of smoke and sweat, and this feels familiar to us as a viewer. Yet Interzone is the same narrow, terracotta alleyways where Lee has his most effective breakdowns as a character, where the stoic face of Peter Weller’s performance is broken to reveal the vulnerability of what remains of his personality after the effects of addiction.

In another sense, it inhabits some of the more bizarre aspects of Cronenberg’s adaptation, especially when it comes to the relationship between our bodies and the external world. Most notably, the different typewriters Lee possesses all turn into talking, giant cockroaches , manifestations of Lee’s experience as an exterminator and his turbulent relationship with his own writing, as well as continuing the frequently used insect imagery that is common among other beat writers too like Ginsberg and Kaufman, as well as Burroughs’ work also. In this sense we see a direct correlation to Burroughs, as Lee begins the film in New York among a beat writing scene, all distinctly bohemian and self-indulgent.

The different typewriters act as different head agents, playing Lee off against one another as he’s becomes convinced he has to write a ‘report’ on the mundane events of his life. I think it’s fairly safe to assume that this ‘report’ is the print copy of ‘Naked Lunch’ as his friends later visit him in the limbo state to ask for the final chapters. Lee has no memory whatsoever of writing this book he’s ‘supposed’ to have written.

Furthermore, one of these manifestations is a fully formed alien creature (see featured image) who originally gets Lee tickets to fly to Interzone when he accidentally kills his partner (more on that later.) One of the most memorable examples of this conflict with the external form is when Lee ,and a man he’s recently met, visits a rich patron in Interzone, whose mansion is home to exotic birds, books and artifacts. While Lee is distracted, the patron has sex with his companion, both turning into a huge, fleshy sculpture that writhes and screams in a bird cage. Cronenberg brings a level of disgust to the visual aspects, but in turn conveys a more pointed degree of the narrative. It’s one that follows systematic drug use, and therefore a journey of a changing relationship with the external and our internal worlds. In some sense it links to our minds, but it also reflects our bodies, the physical realm that we own and experience but rarely control. His style also manages to reproduce the ‘feeling’ of the novel, which in itself is only a very loosely connected series of events which collate to more accurately form an overall impression or image.

I will eventually stop talking about beat writers.

Burrough’s style is one that’s typical of a certain type of beat writer, however his reliance on the abstract surpasses any other I’ve known. While the film replicates this illogical style of progression, it tries to reach a midway point to establish a degree of more traditional character development and therefore a more traditional sense of journey, the story does not follow traditional narrative arcs but it is still notably more coherent than the original text. It’s my personal style of preference, one that feels far more natural and yet lends itself to the more abstract portrayal of our everyday lives, usually reaching the heart of an issue or thought that needs to be translated into a separate logic, before it can be once again translated back into our understanding.

Before long you start to accept that not everything makes sense in this world the way you think it ought to, and that’s what I like most about it. You align yourself with Lee’s mindset as he struggles through intersecting points of reality. You feel comfortable in his room, and feel the shocking melancholy when he’s washed up on the beach after a binge session. We are constantly presented with side characters who talk about events Lee doesn’t remember.

He’s a classic unreliable narrator, but that becomes more than just an overused Lit-class term because you feel so closely linked to him as a character, it becomes an undeniably stressful experience. He’s ironically grounded, and often seems to try and do something resembling the ‘right’ thing. Even when he accidentally kills his partner, you forgive him because the narrative has already established him as the central role for your experience and undermines your immediate moral/emotive response i.e. you know something’s up, something is not quite as it seems.

As you come to this realisation, the film allows you to stick with Lee as the one recognisable factor in a world gone wrong, when all others seem alien and deeply strange. It’s not long before you begin to suspect everyone else in the film of trying to kill you. As a cinematic distinction, Lee is the rope we cling to in spite of all other events.

I’ve realised I’m not done doing weird stuff

This said, the relationship with his partner (a fantastically nuanced performance by Judy Davis) is a memorable motif that runs throughout the film. He accidentally kills her while trying to shoot a glass off her head. However her doppelganger appears in interzone, married to another rich patron and he is convinced to seduce her by one of his many hallucinatory bugs.

Yet the film ends with him trying to rescue her from Dr. Benway, and driving to the new land of Annexia. In doing so, he tries to shoot the glass again in a car and kills her again. This is purely something that appears in the film, as Lee’s justification for leaving America in the book is simply that he needs his next fix, and to get away from international cops.

I could speculate endlessly on this but that, frankly, would be insulting to Burroughs. It is simply, something I think about, as is the idea of Naked Lunch generally. Is the writing grotesque, vulgar and old fashioned? Or is it something else?

Burroughs echoes a well documented criticism from many American authors at this time and after, a definite mistrust in the American government’s approach to traditionally non-American ideals. A McCarthy-esque vacuum of interior development, an infrastructure that, after shaking for a moment, is welded back together by fanatics. The America Inquisition.

Burroughs himself was frequently followed by the FBI, after Naked Lunch was initially banned by a court case upon release. A case that represents the last time in American history that a novel was banned for a decade after it’s publication. On four separate documented occasions, Burroughs was interrogated for supposedly being linked to domestic terror strategies.

As I say, un-American trash.

Drugs, asylum operations, race, homosexuality, whatever you want to pick – American domestic policy developed in reaction to these ‘issues’ has left a shared history of lethal state practise – with race in particular being cited as key factor in the CIA development of internal terror plots i.e. staging terror attacks by using fringe community or religious groups. This is a practice that, to this day, is documented and in use.

Take Dr. Benway in the novel, who hides himself in a factory full of characters seen previously in the film, addicted to the ‘black meat’ and suckling it from alien tubes. He is the centre of a corporate organism, and so the narrative looks more to his representative figure as the centre of corruption, affecting the individuals within the film and their psychological relationship with not just the drug, but the act of taking and having taken it, equally reflecting Benway’s position in the novel as a sadistic maniac caught up in the ‘political’ conflicts of Interzone.

The most terrifying corporate entity, is the one with an empty board room. The one which is self-sustaining.

So, why?

The real merit of the film was in the understatement of its poignancy. It tells a story of addiction in a visually striking and unpredictable world, but also makes a wider comment on personal relationships, and how this ultimately led to Burroughs to writing ‘Naked Lunch’. No, it definitely isn’t a poignant or gentle approach to recovery, it’s priority is style – but does that really mean it doesn’t have substance?

It provides a lot of context for the novel, while creating additional elements that enhance it’s original relevance to the beat movement. The style through which the story is told provides an absurdist methodology as a vehicle for constant movement within the story – you’re permanently unsure of the world you’re in, but vaguely aware of a set of rules that are slowly sinking in the back of your head.

I felt both at home and in turmoil, but wholly engrossed in the narrative. I’ve got a strong affinity for this story , and I can never put my finger on it. It might be because we’ve all had moments in desperation, where we feel ourselves changing. It’s a film that teaches us that judgment is rarely the answer. Those in glass houses etc etc.

Ultimately the drug should never replace the person at the heart of the story. Addiction is still a policy breaker, under-funded and facile in the faces of longer term effects outlasting short term, knee jerk reactionary politics. While this story isn’t a close or methodical drama on this topic, it does tell the story in Burroughs’ way. It remains faithful to what he remembers, what he felt. In turn, it comes close to approaching experience, the end-point of all faslehoods, and something that forces us to shut up and listen to someone else’s experience.

If that doesn’t sell you, the Jazz is also fantastic.

Leave a comment